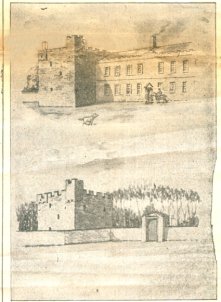

Cresswell Tower and Manor-house

| The following is from a newspaper

cutting found in an old book. I think that it will be of general interest but especially to Stephen Brindle of Cresswell, a visitor to the Border Reivers Website, who had previously contacted me regarding the buildings and had done some early research. Tarras |

|

|

|

The little tower at Cresswell and the story of the "White Lady" by Paul Brown. |

||

|

Cresswell Village looked bonny indeed under a blue sky, and warmed by winter sunshine. High overhead an aeroplane, so far up that the drone of it could only be heard faintly, sped on its way while, thousands of feet below it sea gulls flapped a more erratic course. Far out at sea a merchant vessel moved northward, leaving a long trail of smoke hanging in the still air. It being the “close season” no crowds of holiday makers thronged the grassy banks or yellow sand and, in the homes of Browns and Armstrongs, the daily chores were being overtaken almost without interruption. It was a fresh, clean, happy day, one of those unexpected, and so more welcome, days that this winter has so generously given to us. We come through Ashington, where the main street was crowded by Saturday morning shoppers and where the odour of a slag heap was unmistakable. Lit by the sun, “Mount Ashington” had such pictorial value, that the photographic film was by no means wasted upon it. But, further on, the village, the trees, the tower and the sea and coast at Cresswell made a sweeter picture. Cresswell Tower. The little tower, standing somewhat aloof from the village, is an old friend of mine, although I have only once been inside it, and that was longer ago than it would be wise for me to mention. Glorious days have I known, with boon companions, cycling in that neighbourhood, “when all the world was young.” I do not now remember how it was that we were taken into the tower one afternoon, but in we went and heard again the story of the “White Lady” and saw the quaint lettering, on the stones above and at the sides of the window, forming an inscription, which none of us could read. We were informed that the true interpretation was "William Cresswell, brave hero." As far as I know, the lettering is still there and as difficult to read as ever. I looked up Hodgson’s “History of Northumberland” recently and found that he was inclined to date the inscription to about the end of the 17th century. The William Cresswell, who was living at that time, did not reside in the tower, but in a manor-house, which had been built on to it. I can scarcely think if the inscription is really what we were told it is that he was responsible for it. A gallant gentleman would be unlikely to describe himself as a “brave hero.” Two Manor-houses What the manor house was like I have no idea, neither am I aware that any drawing of it is in existence. A later William Cresswell pulled it down, together with a chapel which was attached to it, and on the same site built himself another mansion. That, too, has gone, although it stood, I believe, until 1840. |

You may form some idea of what it was like by glancing at the upper of the two sketches which accompany this article. When, or why, the Cresswell's ceased to reside in this mansion. I cannot say, but, in 1772, an advertisement appeared in the Newcastle Courant announcing that it was “to let” it being no longer occupy by the Cresswell family. In the course of time the place was tenanted by several working-class families. It was definitely on the decline, but there was a temporary revival when a very distinguished personage took up his residence in it for a brief period towards the end of the 18th century. This was none other than the Duke of Gloucester. Invasion expected. It was at a time when the English people were alarmed about the possible, and, as they thought, probable, invasion of this country by the French. “Boney’s” successive victories on the Continent were making vast changes in the map of Europe and there was a firm belief that he would turn his attention to England. The obvious thing was for Englishmen to prepare to resist him and one of the places where soldiers were encamped was beside Druridge Bay. The Duke of Gloucester, who commanded them, resided, according to a manuscript note I have come across, in the old mansion of the Cresswells. It is added that while there he attended services in the church at Woodhorn. As you know, the threatened invasion did not materialize but, rather more than a century earlier Frenchmen had landed in Druridge Bay and had done a great deal of destruction before being driven back to their ship. It had attacked and pillaged Widdrington Castle, Chibburn Preceptory and houses in Druridge Village, but, as far as I can gather, they left Cresswell alone. Demolished For more than 40 years after the Duke of Gloucester’s visit the old Cresswell mansion stood its ground, when it was pulled down, all except the front door, which is there to this day. You can see it in both of the above sketches. As I stood looking at it the other day it occurred to me that it must be very disconcerting to any ghosts, who were attached to the old dwellings, to see the perfectly familiar door leading, nowadays, to no-where. I wonder what ghosts do in a case like that? I believe that the old house was ghostly enough a place of bare rooms and long passages, where footsteps made hollow sounds, and dark corners might conceal anything. The White Lady, however, was not one of the wraiths that haunted it. |

Her abode was, and still maybe, the Tower. Some twenty years before the house was demolished handsome Cresswell Hall was built, not far away. Now that, also, is disappearing, but the sturdy little tower lives on. The White Lady. The Cresswell's, as I am sure you know, are of ancient lineage. Their’s is one of the oldest families in Northumberland. I have read that there were Cresswells of Cresswell as far back as in the days of King John, but the story of the White Lady, if, indeed, she was a Cresswell, suggests that the family tree had taken root beside Druridge Bay long before that. I may be wrong, but I have always pictured the White Lady as a Saxon damsel in which case she cannot have lived in the tower we see today. She was in love with a Danish prince and that, if she was in truth a Saxon, was a state of affairs not likely to be encouraged by her family. But young ladies in love have, in all ages, been liable to sometimes forget family obligations, which, as any young lady in love will tell you, is a perfectly reasonable course to pursue. This particular maiden, it seems, climbed to the roof of her home one day and scanned the blue ocean in the hope of seeing a sail. It was no ordinary sail she was looking for, but the very special one on which the wind would blow so that the vessel bearing her own Prince Charming would be quickly and safely wafted into Druridge Bay. She saw it too, at first a tiny distant thing, but increasing in size as it drew nearer and nearer to the smooth, golden shore. She saw the pretty, graceful ship beached in the skilful way in which they knew how to beach a vessel long ago. The Prince leapt to the sands and then climbing up the grassy slope, waved as he saw her on the housetop, and came striding towards her. Tragedy--and after. He came alone, as lover would, leaving his men beside the ship. But in the eagerness of a lover’s advance, a warrior’s watchfulness was forgotten. He had almost reached the house, and his ladylove was about to descend from her eerie when suddenly her three brothers appeared. They rushed headlong at the unsuspecting man and, with their swords, slew him before her horror-stricken gaze. She was in inconsolable-her brave prince was dead. She had now no wish to live and persistently refused food she, at last, died from starvation. I do not know whether now-a-night's she is ever seen upon the old tower, but people used so to see her. Can anybody tell me why her spirit walked, or it may be walks? I should have thought that, united in death, the pair of sweetheart would have sailed away in a magic ship to become lost for ever to mortal eyes. It is difficult to think why she has returned again and again to Cresswell Tower, unless-it is a crudely unromantic suggestion-after the spell of her self-inflicted starvation ended, appetite returned, and the White Lady is looking for something to eat. |

Copied as written. Probably late 1939/40.

Cresswell Tower lies on the coast of Northumberland facing the North Sea.